Jocelyn Velasquez Baez entered Wesleyan a math major on the pre-med track. But when multivariable calculus didn’t pique her interest, she started to wonder if she had chosen the wrong path. It wasn’t until she landed in a science in society (SISP) course, that she started enjoying what she was learning. Her courses centered on health disparities and the history of public health, which caused her to begin questioning the very foundations of her pre-med education.

Fast forward 4 years to May of 2023. Baez is a recipient of the prestigious Thomas J. Watson Fellowship and is embarking on a project to explore the role of traditional medicine in ethnic and Indigenous communities worldwide. Baez is one of only 42 fellowship recipients and will be traveling to six different countries to conduct her research.

From the age of eight, Velasquez Baez had known she wanted to be a doctor. It started as a dream that her parents and family friends had had for her, but it quickly turned into a goal of her own. Baez, whose father is from Guatemala and whose mother is from Mexico, had grown up hearing stories of her father’s upbringing as an Indigenous K’iche’ Maya person. Her father’s village was four hours from the nearest hospital and the staff there only spoke Spanish, which prevented them from communicating with Velasquez Baez’s relatives who spoke K’iche’.

It was after hearing those stories that Baez dedicated herself to providing for her ancestral community in Guatemala and representing them when no one else could.

She quickly began to realize, however, that the well-worn path to medicine that she had always intended to follow, wasn’t necessarily the right path for her. She had always pictured herself winding up in a white lab coat curing diseases behind a lab bench. But the further she progressed down the pre-med path, the further she drifted from the traditional medical knowledge she had grown up learning.

“Western science has coopted Indigenous knowledge,” Velasquez Baez explained. “I realized I couldn’t go straight to medical school and that instead I needed to immerse myself in different perspectives and communities to really understand the professional that I wanted to be.”

It was in her SISP courses that she was encouraged to filter her education through her own personal experiences.

But settling into the SISP major didn’t diminish Velasquez Baez’s love for science. In fact, it did the opposite. She still wanted to study medicine, but she was intent on integrating her traditional and familial medical perspective with that of Western medicine. By her sophomore year she had set herself on a path to public health that was strongly informed by her own identity.

Her own ideas about her identity and how she identified were in flux, however. Ever since emigrating to the United States from Latin America, her family had identified as Latino. But, this label had erased Velasquez Baez’s identity as Mexican and Guatemalan. It had also erased her father’s identity as an Indigenous K’iche’ person. In an effort to reconnect with her roots, she stripped herself of previous labels and started identifying first and foremost as an Indigenous woman.

“I started decolonizing my perspectives and tried to take away the identity that was imposed on me,” Velasquez Baez shared.

Relabeling her own identity was an important step on Velasquez Baez’s path to becoming the student researcher and woman she is today.

By the half-way point of her college career, she had clarified her goal as an aspiring physician: to ethically integrate Western medical practices with the cultural and intergenerational knowledge of the Indigenous communities she wanted to serve. But doing this would require truly carving out her own path. And having a mentor to help her do this would prove to be essential.

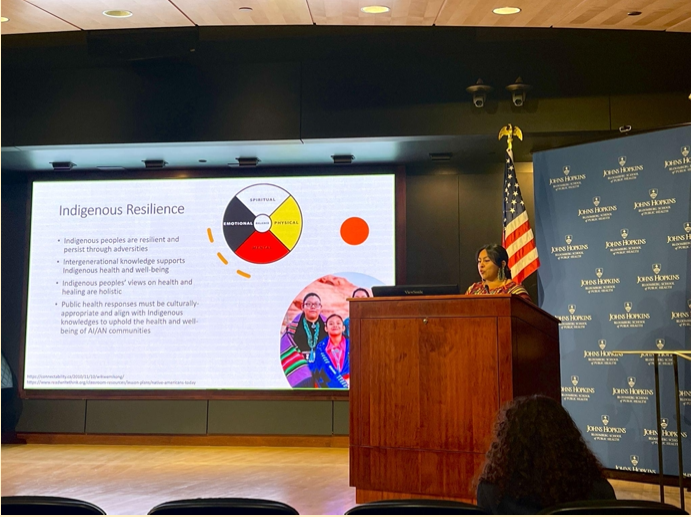

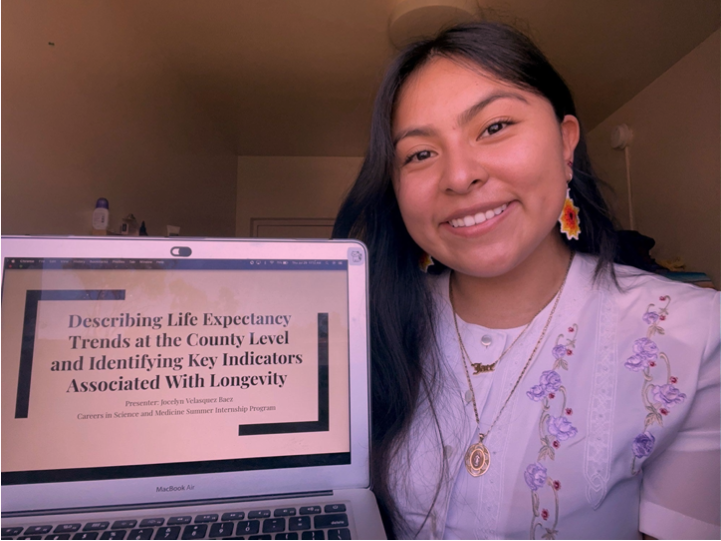

In a research internship Velasquez Baez completed last summer, she was matched with faculty mentor Dr. Victoria O’Keefe, an assistant Professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the associate Director at the Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health, who is a Native American woman herself.

It was under Dr. O’Keefe’s mentorship that Baez learned about something that would deeply inform her research going forward: Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR).

“Community based participatory research is about keeping community members at the same level as the researcher,” Velasquez Baez explained. “[It is about] partnership and each [community member] contributing in every step of the research process in order to achieve one goal.”

After working with Dr. O’Keefe on CBPR efforts, she decided to adopt this methodology when it came to designing her project for the Watson Fellowship.

Ultimately, Velasquez Baez designed a project in which she would explore understandings of traditional medicine within both Indigenous communities and within the greater Western healthcare system.

“I am looking into whether integration or disintegration [of medicine] is ethical or correct,” Baez said in an interview with the Wesleyan Argus. “The Watson Fellowship might help me answer this question, as I can meet different medical practitioners and leaders in communities.”

Next year, Velasquez Baez will be traveling to New Zealand, The Philippines, Nepal, Ghana, Ecuador, and Canada to meet with practitioners of traditional medicine in Indigenous communities. Velasquez Baez is also passionate about highlighting the diversity within the Indigenous groups worldwide.

“Even amongst Indigenous communities, we’re not homogenous,” Baez emphasized. “In Canada, for example, there are multiple different indigenous groups that are all ethnically, linguistically, and culturally diverse.”

On her fellowship, Velasquez Baez will work with a diverse range of ethnic communities to answer her research questions and inform her work as an aspiring medical practitioner going forward. Velasquez Baez hopes to use what she will learn to give back to her ancestral community.

“I want to be a leader and represent my specific community,” Baez said. “I want to take part in the movement to diverge [medicine] from Western ideologies, and set up an Indigenous way of running research.”